Another insight from Jules Henri Poincaré is worth considering, to finish this review of Sean Carroll’s The Big Picture. Recall that Poincaré was a first-rate mathematical physicist in the late 1800s who also contributed to the philosophy of science. He said the only objective reality humans can get any sense of is “the internal harmony of the world.”

By this, he meant that mathematics works so amazingly well in the physical world, and is therefore helpful to science, because it confines itself to discovering the rules of this “internal harmony.” Thus, science would hopelessly flounder in modeling physical systems without math. He thought that human evolution had adapted us to sense this harmony, but that is not the same as knowledge or understanding.

Does the harmony that human intelligence thinks it discovers in nature exist outside of this intelligence? No, beyond doubt, a reality completely independent of the mind which conceives, sees, or feels it is an impossibility.

–from Science and Hypothesis (1902)

Since Poincaré appreciated the intuitive, creative aspects of human intelligence, he might approve of Carroll’s “poetic naturalism,” until he witnessed how fervently Carroll tries to refute the hypothesis of a supernatural realm. His judgment would not come from religious belief, but from his philosophy of science. Like Carroll, Poincaré was raised in a religious family, but later decided to believe in atheism.

As I read The Big Picture, a second time in preparation for this 3-part review, I did think, “Man, he won’t let up!” Yet, his attacks show that his real target is Intelligent Design. He has performed a bait-and-switch tactic. The bait is whether any supernatural realm exists. The switch is not just any supernatural realm, but specifically one in which deities continuously involve themselves in the natural processes of the universe. Any reader will see how Carroll religiously defends atheism, as a committed true believer would.

I suggest below that Poincaré’s internal harmony of the world, which he put in the context of math, science, and the physical, may have a supernatural component. This is pure speculation, but if sensing harmony caused humans to evolve into mathematicians, perhaps it also evolved us into spiritual beings.

some things Carroll gets right

If we ignore his religious motivation, his descriptions of how science gives people good ways to live in the 21st century are worth reading. I highlight his conceptions of emergent perspectives, domains of applicability, and planets of belief, which are all related.

For several hundred years, as scientists argued over and tested their hypotheses, they eventually agreed on some, which would then be termed “theories.” These are a step above because they have withstood extreme scrutiny. However, we can look back and chuckle at how, at each century mark, what scientists often thought were ultimate theories for all time were discarded before the end of the next century.

What did scientists in the 1800s think previous scientists “knew” about reality? Next to nothing! (Their response: We now know what’s really going on.) And how about those of the 20th century, looking at science developed in the previous century? Wrong! Scientists always assume their ideas match ultimate reality, when the passage of mere decades often proves them wrong.

the scope where science works

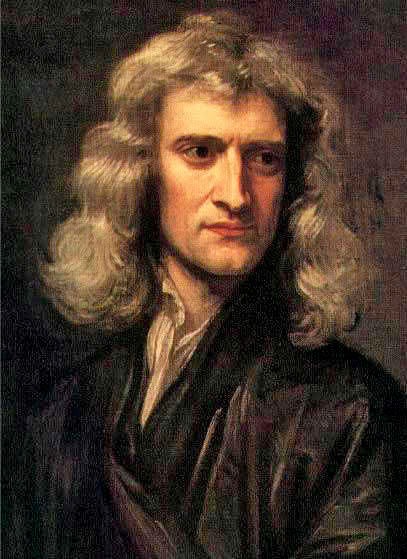

Carroll’s term domain of applicability is helpful for our understanding of how science evolves. Take the mechanics developed by Isaac Newton. After Einstein, we know that Newton’s methods have a certain limited domain of applicability. We build bridges using Newton; we design satellite GPS (global positioning systems) using Einstein.

Later researchers concluded that their predecessors’ main error was misidentifying the scope of their theories. In other words, the scientists were more wrong than their theories were.

Newton defined space and time in a way he thought was true of Reality, so he felt his mechanics would apply everywhere, all the time. He was wrong, but his methods still worked in the proper context.

We discovered Newton was mistaken in his ontology only after Einstein’s new physics. Knowing he was mistaken, we now adjust our use of the earlier scientific methods to a limited domain of applicability. Most earth-bound engineering projects use Newton’s mechanics. The additional insight of General Relativity on the Earth’s surface is negligible.

Nearly concurrent with the revolution caused by Einstein was a similar one concerning Euclid. We still use his geometry in a limited domain of applicability (Earth’s surface), but we know that Euclid’s postulates, thought to be true about Reality, were not. His geometry is not wrong, for a specific domain of applicability; his ontology was wrong.

We can see why scientists advocate finding methods that work without trying to prove the ultimate reality underneath. They tentatively assume their models match the underlying reality, but are always prepared to be proven wrong.

science in common use

Carroll’s term emergent is also helpful in understanding how ordinary people can use science without being a math or physics whiz. Yet, we can point out a humorous aspect of his word choice. Emergent methods, Carroll contends, come from deeper, better-understood microscopic particle behaviors. Yet, everything emergent existed before the deeper theories were even imagined. To be more precise, Carroll would have to say the ideas were retroactively emergent.

The most familiar example is our measurements of air temperature and pressure. Humans knew these aspects of our daily lives long before knowing that air is composed of a combination of gaseous elements, each with moving molecules and atoms.

Similarly, we can understand why people might protest spending billions of public funds on particle accelerator facilities searching for bosons, gravitons, or dark matter particles when physicists have not suggested an emergent day-to-day use for that knowledge.

Carroll wants us to be impressed with the Core Theory, saying it will never be overthrown. He talks about emergent aspects as valuable, but of less intrinsic importance. However, our only current emergent science is of the retroactive type. Carroll does not show us anything we do in real life that has emerged from quantum mechanical understanding.

incorporating aesthetics into belief outlooks

Carroll rises above the typical atheistic scientist because he acknowledges and celebrates non-scientific ways of helping us live better.

Although he pushes atheism throughout the book, on p. 91 he admits, “We have every right to give high credence to views of the world that are productive and fruitful, in preference to those that would leave us paralyzed with ennui.” His solution is poetic naturalism.

Scientists debate competing hypotheses as they investigate how the natural world works. Similarly, we can all compare aesthetic expressions. What makes one poem better than another? Is some art intrinsically better or merely subject to opinion or taste?

Carroll suggests that one method of judging is whether things fall together into a planet of belief. I find this concept insightful, but am wary of one aspect Carroll seems to think is very important: consistency.

I don’t contend that what Carroll looks for is entirely unwarranted. But, as Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said:

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

I think scientists are less likely than many humans to fall for foolish types of consistency, but those in professional creative endeavors are even less vulnerable. One cannot strive for consistency and be innovative, fresh, interesting, and attention-grabbing, as opposed to banal, same-old-same-old, been-there-done-that, boring, repetitive, or lacking imagination.

We should ask how much it matters whenever we are challenged to lower credence for some value we hold based on consistency. When two people discuss the same concept using radically different metaphors, we have value judgments to make, but consistency is not one of them. They may both be valid, but approach understanding from various angles. Or one person may feel recognition or meaning from a particular metaphor due to their personality or experience, which differs from that of others.

holding multiple maps and metaphors

I suggest that many people choose atheism because they are not impressed with the maps and models put forth by religions to help guide humanity. Spiritual people need to allow challenges to their ways of thinking, which might advance spiritual evolution.

Physical evolution has been effective for millennia, but spiritual evolution has lagged. On the other hand, note that we no longer believe in the Greek or Roman gods or astrology. The evolution from polytheism to monotheism is a spiritual improvement. Carroll argues that evolution should go from many to one to none.

Spiritual progress is less about how we imagine heaven or Olympus and more about how our actions benefit humanity. An individual’s actions say more about what they really believe than their claims of religious adherence. Of course, we can also suggest that religions intolerant of other beliefs or even calling for the murder of non-adherents should be judged as low-quality belief systems.

I agree that a stable planet of belief cannot (for example) hold that both polytheism and monotheism are true simultaneously. However, by comparing various religious practices, we can observe whether or not they arise from incompatible beliefs.

For example, does the Mormon appreciation of family values arise from believing in a plurality of gods? They claim to follow Jesus’ teachings but also think God, the Father, has a wife, was preceded by another god (Grandfather?), and that human followers become gods themselves after death. If subsequent divine revelation showed Mormons that none of these extra gods exist, would that cause them to jettison family values? We might suggest that any faith look at what matters most about their beliefs, and weed out less worthwhile aspects.

Maps, models, and metaphors can illuminate understanding in different ways. We can choose the ones that work best and ignore those that are useless.

a radical Christian perspective

The word radical has sometimes been used to disparage hippies or other unconventional people, but it relates to the word root. The rose bush is an apt metaphor. Rose care aims to produce beautiful, fragrant blooms, but it also includes extensive pruning in the off-season. The plant seems to appreciate going back to its roots each year.

As a follower of Jesus, I contend that we must be wary of adding to what Jesus taught or ignoring what we find inconvenient. If you are told that some action is Christian, ensure it seems compatible with something Jesus said. Remember that what people believe is revealed by their actions. If you claim to be a Christian but continuously spew hate speech at other people via social media, this shows that you are two-faced. You say you believe something that your actions contradict.

list of my unconventional Christian beliefs

- The writers of the Bible were human and subject to mistaken thinking. (The Creator did not guide their writing instruments.)

- The Biblical texts are subject to interpretation and cannot be said to have a single “correct” meaning endowed by religious authorities.

- The Creator made Reality to run on its own without any supernatural intervention.

- The “Holy Spirit” is not a ghostly invisible being that takes up space and moves from place to place.

- Every atom and every aspect of the physical world is part of “the being” of the Creator, yet the physical is not the entirety of the Creator.

- Our interaction with the physical world is one way we interact with the Creator, whether we know it or not.

- Our soul or spirit is not a separate thing that takes up space or resides in a special place within us.

- Our spirit is a combination of our thinking and behavior, and is encouraged by community engagement.

- Prayer is an attempt to align our spirit with the life-affirming point of view of the Creator.

- Miracles are possible because the Creator can intervene at any time.

- Jesus performed miracles because the Creator granted him authority.

- Ordinary people cannot perform miracles because the Creator does not usually want to tinker with the natural laws he initially established.

- No one who does not know the Creator in the way Jesus did should expect to be granted authority to perform a miracle.

- Stories of miracles performed by Catholic saints or other humans are seriously questionable (though not impossible).

- What we call evil is allowed by the Creator, even though it manipulates physical aspects of himself, because he grants autonomy to created beings and desires to let nature take its course.

- The Creator does not need angels, demons, or the archangel, Satan. Both good and evil arise in human hearts without encouragement from ghostly beings (stale metaphors?).

- It may be that the Creator chooses to impose some self-limitations, such as not looking at the future, but enjoying watching it enfold moment by moment.

- The teaching of Jesus is so profound and positively impactful that following him is the best way to live (following him over and above religious dogma).

credence for believing in Jesus

Carroll might try to say that the Biblical writings about Jesus should not be believed. Many atheists try to undermine Christianity by searching for evidence that a historical person we now call Jesus did not exist, or did not claim to be a son of God, or did not perform miracles. They think New Testament scripture was an intentional program of deception.

I find it interesting that, whatever happened back then near what we now call year zero, the events must have been extraordinary. Not simply out of thin air did a subversive grassroots religion arise within the polytheistic culture of the Roman Empire and grow to outlive its fall.

Following Jesus’ teachings helps the world become a better place. Many people and organizations may take evil actions in Jesus’ name, but we should not dismiss the value of his teachings based on actions that fail to follow them. No one should be surprised that humans are prideful, power-grubbing, self-serving, pleasure-loving creatures. The scriptures shed plenty of light on these human deficiencies.

Both atheists and believers of various religions can do things that either help or harm society. Comparing models, maps, and metaphors, without fallacious, a priori judgments, is a valuable way to proceed. Atheists should notice that they can tend to behave like religious people, in defending their own points of view and trying to shoot down alternative beliefs.

conclusion of the review

Many people today are taken in by scientific imperialism. Young adults, especially, have grown up wary of religious talk. Some avoid discussing spirituality, as if exposing themselves to such ideas could infect them, and that any religious ideas may be equivalent to drinking the Kool-Aid of a cult. Yet, more and more people are also drawn to seek a spiritual higher purpose, sensing the eternal harmony.

Science is a valuable human endeavor, but not the only way to discern truth and find advantageous ways to live. While I applaud Carroll’s book for its readability and descriptions of how ordinary folks benefit from science, I warn readers that his continuous advocacy of atheism is another religion in disguise. Look around the web and peruse books and articles by atheists. They are all about evangelism, trying to draw others to their beliefs. You will notice similarities to religious preachers, acolytes, and proselytizers.

Still, talking with people who don’t believe the same as you is worthwhile. We should all compare maps, models, and metaphors, and stand up for those we think are superior. Yet, don’t be like the monkey that refuses to look around, hear, or sample ideas others offer. Instead of dividing ourselves into insular tribes, why don’t we make a community of the entire human family?

Optional links: Go back to the intro of this review or to the second installment.