For the second installment of this review and in the spirit of “poetic naturalism,” I refer now to one of my favorite books of all time: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, a 1974 novel (which covers neither of those subjects). Here is only one story detail: the narrator travels real roads in an archeological quest to rediscover valuable artifacts of his former crazy self (whom he calls Phaedrus). He had gone through now-outdated electroshock therapy and was only vaguely able to recall some thoughts of his past, possibly genius self.

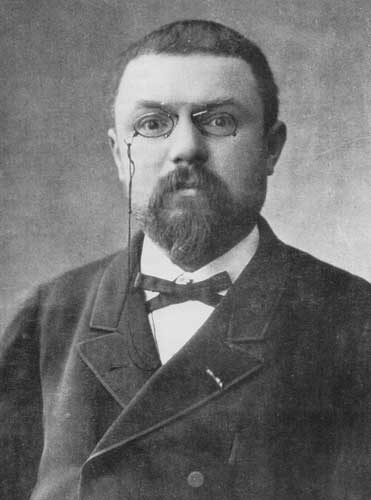

Phaedrus was interested in the history and philosophy of science, which drew me in. I probably first read “Zen and the Art” in 1980. Chapter 22 discusses the French polymath from the turn of the 20th century, Jules Henri Poincaré.

He was a first-rate mathematical physicist who contributed to numerous fields, including relativity. Poincaré was also interested in the philosophy of science and realized the impact of uncertainties thrown into traditional deductive reasoning by the then newly discovered non-Euclidean geometries.

Jules Henri Poincaré

Poincaré would disagree with Carroll about whether we can know ultimate reality. From his book, Science and Hypothesis: “That which science captures are not the things themselves, but simply relationships between them. Beyond these relations, there is no knowable reality.” This and the following quote of Poincaré come from page 145 of a nonfiction book I highly recommend, Science Wars: The Battle over Knowledge and Reality, 2022, by Steven Goldman. Also available as an audio course, taught by Dr. Goldman.

That second quote from Poincaré is: “The purpose of mathematical theories [in science] is not to reveal the true natures of things. Such a claim would be unreasonable. Their only goal is to coordinate the physical laws that experiment reveals to us, but that we could not even state without the help of mathematics.”

This statement became increasingly salient as the 20th century progressed. Science (particularly quantum mechanics) became so abstract that no physical analogies could be imagined to help understand it. Investigators needed to become comfortable with purely abstract mathematics.

.

.

Referring back to Zen and the Art, I note that Phaedrus was impressed by how Poincaré identified numerous intuitive and creative aspects to the work of scientists. In making observations, collecting data, and proposing hypotheses, Poincaré said, p. 264, “Which facts are you going to observe? There is an infinity of them. There is no more chance that an unselective observation of facts will produce science than there is that a monkey at a typewriter will produce the Lord’s Prayer. The same is true of hypotheses. Which hypotheses?”

Poincaré felt that the most successful scientists were ones who not only had math skills, but also had intuitive insight and creativity. From p. 267 in Zen: “The true work of the inventor consists in choosing among these combinations so as to eliminate the useless ones, or rather, to avoid the trouble of making them, and the rules that must guide the choice are extremely fine and delicate. It’s almost impossible to state them precisely; they must be felt rather than formulated.”

Coincidentally, within a decade or so of Poincaré’s musings, a scientist would produce a revolution in physics using these same creative instincts. Einstein was said to have childlike curiosity and rebelliousness, not confined by the typical unconscious walls many adults build around their thinking. Einstein on this subject: “In my opinion, the answer to the question [of whether people can fathom reality] is, briefly, this: as far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.” (Science Wars, p. 110.)

“All our theories are inescapably dependent on definitions, assumptions, concepts, and metrics that are not logically necessary, nor are they derived logically from data. They rest on conventions that are freely adopted by the scientific community on the basis of convenience or advantage: ‘Experience… guides us by helping us to discern the most convenient path to follow. [Poincaré]’,” from Science Wars, p. 145.

what other scientists have said about science and reality

A century before Poincaré, scientists disagreed about what heat was. One hypothesis suggested that all matter has a weightless fluid (caloric), and heat is the escape of that substance. The competing theory was that heat in matter was from friction due to the movement of small particles comprising the matter. (The idea of atoms had been posed by the Greeks, but was not re-established until later.)

Another Frenchman, Joseph Fourier, like Poincaré, a mathematical physicist, derived a way to compute heat behavior independent of what heat might “actually be” or how its essence might eventually be described. “What was striking about this theory was that Fourier explicitly dismissed the ontological question of what heat was as irrelevant. A scientific theory need not disclose reality. …Fourier said that his theory accurately described how heat behaved independently of what it was.” (Wars, p. 105.)

A German contemporary of Poincaré, Ernst Mach, also incorporated a philosophy of science into his work. As a highly respected and productive scientist of his time, he considered metaphysics completely beyond the realm of science. “Based on his own extensive experimental studies, Mach argued that what we call the external world is actively constructed by the senses and the mind unconsciously. The object of our conscious reasoning about the world is not as it is out there.” (Science Wars, p. 127.)

Our thinking can only construct a mental world using metaphors and mental models. Mach’s view has been restated recently by Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow in The Grand Design (2010). As mentioned in the intro post of this review, they introduced the term Model Dependent Realism, suggesting that science only relates to reality through models. The model is not a one-to-one correspondence with reality, but only works with behaviors or aspects of interest to the modeler. This way of thinking about science is similar to language being metaphor-dependent.

continued review of The Big Picture

These past respected scientists would say that Carroll has every right to speculate about whether atheism is the best way to think about reality, but that he would be disingenuous to claim that science backs him up.

This second review installment begins with these previous eminent scientists, partly to show that Carroll uses his prestige as a scientist to lend weight to his ontological claims. Many first-rate scientists say that metaphysics is an unrelated pursuit. However, today we have a public phenomenon called “scientific imperialism.” The success of science over the past century has been so complete, and all humans have benefited so much, that many people think the only valid way to know anything is through science. Writers of common interest books about science can take advantage of this prestige and sometimes use it to claim knowledge that is, at a minimum exaggerated. Carroll uses it as a proponent of atheism. One might ask, “Is Carroll a capable scientist or is he more of a showman and communicator?”

Although his writing is very understandable, Carroll also takes advantage of ambiguity in language. As discussed in the introduction to Wars, p. 2,

Words matter. They matter because words often carry connotations, presuppositions, and value judgments that shape how we respond to them. Consciously and unconsciously, we respond very differently to knowledge than we do to belief and opinion. We use each of these words with the intent that they have different effects on listeners and readers.

Thus, the words, knowledge, belief, and opinion can be imprecisely used and taken by others to connote something different than intended. But people thinking scientifically can feel they know something in a way that is stronger than belief or opinion. This is one way Carroll has an advantage in his book. Merely by being a scientist, he can seem to have more authority. Note that a discerning reader could also be wary of other books and articles written about science for the general public.

Sistine Chapel ceiling by Michelangelo. photo credit: bengal*foam on flickr

abductive reasoning

His use of “abductive reasoning” can also be called deceptive. It invokes logic, as do deduction and induction, but is an acceptance of an uncertain answer based on “the weight of evidence.” It is often called the “best explanation” of competing explanations, yet it still suffers from the Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent. This is an important concept, so I provide examples, besides the Wikipedia link.

Example 1 of the fallacy of affirming the consequent:

Given the logical statement:

If I flip the switch near the door,

then the ceiling light will go on.

Fallacious reasoning would be to say:

I flipped the switch and the light did not go on.

Therefore, the light switch is broken.

Why is this wrong? Because many other situations may cause the light to not go on. You cannot deduce that the switch is broken when the light does not work.

Example 2:

Given the logical statement:

If the car runs out of gas

then it will no longer go.

Fallacious reasoning would be to say:

The car stopped running.

Therefore, it is out of gas.

As in example 1, many other situations may cause the car to stop running.

How does abductive reasoning fall into this fallacy? A given hypothesis suggests the causes of an observed phenomenon. People tend to think that greater numbers of empirical observations show accumulating evidence that the hypothesis is correct. However, no number of observations can rule out that a particular observation may have an altogether different cause.

To avoid the fallacy, real-world hypotheses would have to be stated this way: My explanation and only my explanation describes the cause of the observed phenomenon. Clearly, all experience is contingent and can never be considered universal, so nobody suggests hypotheses with that claim.

Bayesian reasoning

In the review introduction post, I linked to a very good YouTube video showing how Bayes’ Theorem works when statistical information is available. But the same idea can be used in a more intuitive way, without the need for probabilistic data. Of course, then it is less purely mathematical and more open to bias and opinion.

Recall from the previous post that the theorem involves a statistical equation with a scale between zero and one. These endpoints are equivalent to certainty, with zero representing a belief that cannot be true and 1.0 for a belief that cannot be false. If a proposition has, to begin with, no evidence one way or another, then the Bayes value is 0.5.

Richard Carrier has a good explanation of the differences between Bayes’ Theorem, Bayesian reasoning, and Bayesian epistemology. He says that normal human reasoning is Bayesian and that healthy human brains are wired to look for accumulating evidence for or against anything we are tempted to believe. Of course, we are also vulnerable to fallacies and belief of nonsense.

Our innate, intuitive belief-forming processes, and our perception—the way our brains decide to model the world we live in from sensory data (and even, model ourselves, who we are and what we are thinking and feeling, from internal data)—follows a crude Bayesian formula encoded in our neural systems. Probably because natural selection has been pruning us toward what works. And really, Bayesian epistemology is it. Any other epistemology you try to defend, either can be shown inadequate, or ends up Bayesian the moment you check under the hood.

So, we regular folks do this thought processing naturally in roughly the following way:

- We believe things mostly “on the fly,” trusting our mental capabilities without stopping to analyze the evidence in depth. This is subconscious Bayesian reasoning.

- If we take time to think more deeply about our beliefs, we usually already have a tentative belief in mind. (This is not a bad thing.)

- If we want to hypothetically “start over,” we can set Bayes at 0.5, and then consider evidence to raise or lower our credence for a given belief.

- Gathering any particular evidence, we must assign some decimal value (if using the Bayesian scale) to adjust our credence. Assigning this value is entirely intuitive. You can decide whether evidence is very impactful or minimally so.

- To have the best chance of success, we need to assign defensible values to evidence. The values should be reasonable, not fanciful.

- Ultimately, given inevitable uncertainty, we can accept a belief because we see no harm in it.

Carroll’s use of Bayes

He suggests that we can use Bayesian reasoning to decide about religion. At the bottom of p. 81, he says,

Consider two theories: theism (God exists) and atheism (God doesn’t exist). And imagine we lived in a world where the religious texts from different societies across the globe and throughout history were all perfectly compatible with one another—they all told essentially the same stories and promulgated consistent doctrine, even though there was no way for the authors of those texts to have ever communicated.

[If the above is true, then it provides strong evidence in favor of theism, but if it is not true,] it follows as a matter of inescapable logic that the absence of consistency across sacred texts counts as evidence against theism.

Carroll might hope his reputation as a scientist would cause you to swallow his argument without much thought. But look at what he has done, because it is deceptive. First, he sets up the opposing theories (which should more precisely be called hypotheses) as either God exists or doesn’t. But people have preconceptions about God (if he exists) that Carroll wants to exploit. The assessment should not contain anything about what this god or gods would be like. A better formulation would be that theism posits a supernatural realm of some kind, and atheism (as Carroll has said) posits no realm other than the natural.

Secondly, Carroll asks us to think of all the various hypotheses across the globe and through the millennia that have tried to imagine what the supernatural realm might be like. Various of these are identified with religions. Some, like astrology, had been considered equivalent to a science for centuries. But all of these speculations are human-imagined hypotheses.

If Carroll is serious that inconsistency across hypotheses is a reason to throw out all hypotheses, even if one or two happen to be pretty good, he would be laughed out of the auditorium. More likely, he is being tricky rather than stupid.

If we apply Bayesian reasoning to the question of supernatural versus natural, we will find ourselves stuck with no evidence one way or another. Carroll might try to fool us with the fallacy of affirming the consequent:

If God exists, then we would find some evidence of him.

We find no evidence; therefore, he does not exist.

Do you see the faulty reasoning? The fact that we find no evidence of a supernatural realm does not prove it doesn’t exist. One possibility is that this god or gods might not choose to provide such evidence.

I am reminded of the early days of Soviet space exploration, when cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth and is said to have radioed back something like, “I have found no god up here!”

To throw out useless hypotheses is how science progresses. And also, how any of us progress in our lives, as we make guesses about things and find out whether they were good guesses or not. As Poincaré said, the creative and wise thinkers try to avoid making unhelpful hypotheses in the first place. To laugh at the hypothesis that the Earth may contain centaurs or unicorns does not mean other hypotheses about animal life can’t be correct.

In light of his atheism, another statement of Carroll’s is humorous. He says, on page 82, “all evidence matters.” But since theism says “there’s something” and atheism says “there’s nothing,” the only thing an atheist really cares about is the lack of evidence.

Another example of Carroll’s reminds me of Yuri Gagarin’s comment that he didn’t see any god out in space. But this time, we go into the microscopic realm. Many religious people feel that communication happens between themselves and the supernatural realm. And many people believe that our connection to the supernatural is through our “soul.” This is a metaphor; we don’t know if we have something in our bodies that connects to the supernatural, but it is a way of describing how we feel.

On p. 212, Carroll says current scientific understanding makes mind/body dualism all the more difficult. “To imagine that the soul pushes around the electrons and protons and neurons in our bodies in a way that we haven’t yet detected is certainly conceivable, but it implies that modern physics is profoundly wrong in a way that has so far eluded every controlled experiment ever performed.”

A humorous response would be to say, “You can’t hook a person up to detecting machinery any random time and expect to find a spiritual particle. You’d have to wait until they sense the Holy Spirit!” But of course, why would the Spirit need to use a particle? Again, we are back to speculating about what the supernatural realm is like, not merely whether it exists or not.

If we agree with Carroll that mind/body dualism is wrong, that mind and body are inextricably bound together, he might ask, “Then what is the soul?” To which we can suggest numerous hypotheses, such as the following:

- Maybe there is no such thing.

- Maybe the soul is only something like a memory location in God’s mind.

- Maybe what we call our soul is a storage bank in the supernatural realm that keeps track of who we are and our lifetime of experiences.

- Whatever it might be, the soul does not have to have any physical location in the world.

Throughout his book, Carroll makes arguments meant to help us lower our credence in the existence of a Creator. The arguments boil down to evaluating hypotheses about the nature of the supernatural. Like scientists, spiritual people use metaphors, maps, and models to try comprehending what we sense and talk with others about it. Comparing hypotheses and finding the most useful ones is precisely what both scientists and spiritual people should do. Again, advocating that one hundred hypotheses are useless or ineffective is no evidence that some hypotheses are not much more convenient and insightful.

Since Carroll starts with the assumption that no supernatural world exists, he concludes that not finding evidence in the brain of something other than physical particles, entitles him to conclude: “And there is no immaterial soul that could possibly survive the body. When we die, that’s the end of us.” Maybe. But maybe not.

the “closed system” of the natural realm

The “science” of astrology was formulated in Babylonian times, before the discipline matured enough to realize that it needed to confine itself to only natural explanations. This can seem obvious to us today; we don’t remember the frequency of invoking supernatural causes for things right up into the 20th century.

Even if a supernatural realm exists, the work of science is to determine how things work naturally, as it has been set up to go on its own, according to physical laws invariant over time and space. Even if miracles are possible, meaning interference in the natural realm by the supernatural, scientists have to ignore them. Scientists don’t need to try to explain them because if miracles are outside of the natural system, then they are outside of what science is about.

In chapter 16, Carroll contends that other ways of determining reality exist besides science, implying music and other artistic endeavors. But he also includes math and logic as non-science examples. On page 133, he says that some scientists make the mistake of saying that science only deals with the natural world. Carroll says science doesn’t care what the natural world is; it is concerned with truth. This stance is fundamentally misguided.

Thus, Carroll criticises the National Academy of Science for publishing the following,

Because science is limited to explaining the natural world by means of natural processes, it cannot use supernatural causation in its explanations. Similarly, science is precluded from making statements about supernatural forces because these are outside its provenance.

Carroll says, “not so,” implying that if the supernatural exists, it will eventually be worked on by scientists interested in whatever exists. Again, this point of view is vehemently opposed by many scientists. The trouble Carroll will face here is that he’d have to give up the idea of “closed systems” upon which so many scientific laws depend. Whenever the great conservation laws are stated, they include the phrase, “in an isolated system” or “within some problem domain.”

From NASA, for example, the Law of Conservation of Momentum is stated as follows:

The conservation of momentum states that, within some problem domain, the amount of momentum remains constant; momentum is neither created nor destroyed, but only changed through the action of forces as described by Newton’s laws of motion.

If the supernatural realm turns out to be non-physical, but capable of occasionally interfering physically with the natural world, Carroll would have to find an entirely new science that deals with these exceptions. But his claim of, “if it exists, we’ll find it” is not sincere, since he believes it doesn’t exist.

the bottom line of Carroll’s arguments

He thinks that any interference of the supernatural realm into the natural would have to obey the laws of physics and involve forces or particles that are theoretically detectable. What if that simply is not the case?

For example, imagine how Jesus might have been able to turn water into wine. Carroll thinks if a scientist were there and could have hooked a detector to the fluid in the jar, they would have detected sub-atomic particle movements, or maybe a sudden infusion of alcohol molecules from the air, etc. We could ask why the Creator would need to begin the supernatural interference at the ingredient level.

If the Creator behaves like a cook and the natural world is his kitchen, he would gather ingredients and use an oven or stove to cook up a dish. Our amazement would come from the speed with which he does this work.

Or the supernatural interference could be that what was water instantly became wine. Carroll’s assumption that the natural world is all that exists prevents him from imagining that anything could happen without some duration of natural processes.

In the final post of this review, I will describe my take on Christianity, which stands up well to Carroll. I do not think the Creator is interested in providing evidence of his existence that a scientist would detect (nor an advocate of Intelligent Design).

conclusion of the 2nd post of this review

I refer to page 300 of The Big Picture, where Carroll has argued against a particular theist idea. Some have suggested that “quantum indeterminacy” is where the Creator might intervene. This is apparently an Intelligent Design idea, which I suggest is utterly misguided.

Physicists say that any particular state of quantum particles cannot be measured precisely but can only be obtained using probability. Intelligent Design apparently says, “Ah-hah! The Creator could intervene at that level, and the physicist would not be able to detect it!”

Carroll’s response on page 300 is the following:

Quantum indeterminacy doesn’t offer the slightest bit of cover for those who want to make room for God to influence the evolution of the world. If God micromanages which outcomes are realized in quantum events, it is just as much an intervention as if he were to alter the momentum of a planet in classical mechanics. God either does, or does not, affect what happens in the world.

The problem for theism is that there’s no evidence that he does. Advocates of theistic evolution do not make a positive case that we need divine intervention to explain the course of evolution; they merely offer up quantum mechanics as a justification that it could possibly happen.

I heartily agree that Intelligent Design can be shot down this way. The Universe was set in motion without requiring any intervention. I suggest that the Creator does not need to continuously guide the natural world, but can intervene supernaturally at any point. I contend that such intervention is rare, as concerns physical miracles, such as Jesus walking on water or raising Lazarus from the dead. I do not say those miracles were impossible. I think the day-to-day intervention of the Creator is through people’s thinking. Even so, the Creator lets natural processes operate on those minds without intervention so that people have to deal with uncertainty, fallibility, and pride, among other things.